Story: Wanderer Overlooking The Sea Of Fog

By: John Michael Flynn

Christmas was a week away when Tillman Grossklag found Claudia Ruden face down in vomit on the floor of her Manhattan apartment. Tillman was the only person Claudia had entrusted with a key.

Tillman removed the emptied Ambien bottle from Claudia’s hand. He turned off the cd of Dvorak’s New World Symphony that was skipping on her stereo. Then he phoned an ambulance.

Five weeks later, he reminded Claudia that if he’d arrived an hour later, her suicide attempt would have succeeded.

“But it didn’t,” she said.

“So it’s fate,” he said. “You’re supposed to be here.”

Claudia said no. She believed in challenges, and free will. Not fate.

Tillman said prove it.

“Pay for my ticket to Germany,” she countered. “I’m off to Berlin for the film festival. Afterwards, I want to see Hamburg. You’ve told me so much about it.”

“Okay, but no cell phones,” said Tillman. “Just you and the city. My city. That’s challenge enough in winter.”

Tillman had work to finish in Manhattan, but he’d screen and inventory Claudia’s calls. Claudia could stay in his Hamburg apartment. “Until you lose your need to need,” he said.

“So you’re my gatekeeper?”

He nodded. “I’ll see you in Hamburg in about a month.”

***

Hamburg’s streetlights cast a roseate sheen over Isestrasse as Claudia walked from the Eppendorfer Baum train station. She had reached a bridge where, like Dvorak in Manhattan, she could watch trains. Outlandish, mercurial, she and Dvorak were alike. She could jump, too, and blame her deathwish on her mother. Poor Mom. The woman had lived in boxes that fitted within each other like Russian nesting dolls.

Better to blame her unhappiness on Elaine for dumping her. Claudia could blame Barbara, as well, who’d run off with Monica to Seattle. Those two had married. Barbara wore flannel shirts and prepared stews. Monica trained security analysts.

At least she’d made it to this year’s Berlinale Festival.Charlotte Rampling, whom she adored, had headed its international jury. The year before, a documentary about Moroccan women – one of six Claudia had helped produce during the past twelve years – had earned her pats on the back and polite applause after a Q and A, but nothing more, least of all funding offers for new projects. When she’d left last year’s festival, she’d felt empty, neglected, and it had set the tone for the year. She’d had savings to live on frugally, but no forward momentum or a project to believe in.

“It’s not where I want to be,” she’d told Tillman.

He’d said, “Then it’s where you should be.”

She’d hoped to feel discovery in Berlin, where alone in tiny screening rooms she’d surrendered to bouts of sobbing. Her favorites had been classics from a retrospective called Dream Girls: Film Stars Of The Fifties. Perched in CinemaxX 8, she’d marveled over Crawford in Johnny Guitar, a gem she’d once prized on VHS when managing a Kim’s Video store. She’d seen Rossellini’s Viaggio In Italia for the first time – falling in love again with Ingrid Bergman.

Some of the newer films had been incredible, and should have inspired her. They hadn’t. She’d felt unrelenting dread. Movie attendance was still plummeting. Few beyond an esoteric circle knew the work of the German genius, Jürgen Böttcher. Earnest, unheralded artists made courageous films all over the globe, yet who saw them? To worsen matters, it was Mozart’s 250th birthday, and she disliked Mozart for the same reason she disliked reggae. Too damn optimistic.

Berlin had felt forced, a necessity. Hamburg, on the other hand, was surprising her. Quiet, easy to walk, she’d met the ghost of her great-grandfather Herman, a pediatrician who had hanged himself.

Herman told her: You’re right, Claudia.There is no fate. So risk changing yourself.

***

No phones. Winter silence. Recuperation. Her therapist had thought it wise, but she’d warned Claudia that suicidal impulses would return.

Embrace them, said her therapist. Then walk them off.

***

A union lighting tech based in Brooklyn, Tillman had been raised in the Grindelberg neighborhood of Hamburg. He recharged between pressured show-biz gigs by visiting the flat he owned in his mother’s building off narrow Brahmsallee. His was on the fifth floor. Mom’s on the eighth. They lived close to Hamburg’s Abaton neighborhood and the State University, an area bombed by Americans during the Gomorrah campaign of World War II.

Saying goodbye at JFK airport, Till had given Claudia a daybook. Inside it, he had paraphrased Nietzsche: If you have a what-for in life, you can stand almost every why.

Under Hitler, Till’s Mom had lost all her remaining family. Till meant something darkly unique whenever he remarked, “It’s just Mom, me, and everyone else.”

Claudia wished Tillman had come with her. Wished she could phone him. She glanced behind her. Followed? No. This was her habitual Manhattan paranoia. She told herself she didn’t need Tillman. Didn’t need a cigarette, either. Still, she lit one up.

In her wool cap, shoulders bunched, she watched her breath. At 41, she was nearly halfway to the end, older than her mother when she’d died. Weak arteries: another Ruden curse. Her father died at sixty. Ruden men had been mariners and doctors. The women: teachers.

Why fear death in a city with a nightclub like Fabrik, where Oma Hans was on the bill? Where a blues club featured Alvin Lee, and Mitch Ryder – both all but forgotten in the States. She liked knowing that Germans revered old-school music more than Americans did.

No need to phone Till. She could be more than another lonely itinerant without innocence on her breath. She had ghosts. She had bridges. She had trains to watch.

***

How she rode those city trains. Per her therapist’s suggestion, she kept a journal, using the daybook Tillman had given her. On the U1 line, the white cars with TV monitors and pink and lavender upholstery reminded her of Hong Kong trains. German trains never ran late. Announced clearly, each stop was shown on monitors. She liked best the striated aluminum trains with red doors headed for places with names like Bambek.

She wrote: Covered in flames I make my way from the prisons of mind through chambers and tunnels into quiet places I deny as home. What’s the point? I don’t know. Who does?

She wrote a description of the stone steeple tower of the Haupt-Banhof with its lit clock and tower that resembled a smaller version of the lighthouse she’d seen on the harbor. These places had survived American bombs, but much around them – from the Saturn dealership to the Karstadt department store to the Budnikowsky shop – appeared shockingly new.

She bought herself two pairs of leotards at Fitness Company. In such wet cold, she’d wear one pair to bed, and the other beneath slacks or jeans. She hadn’t packed well, at all.

Loitering in one neighborhood, she watched Turkish cab drivers seated at the wheels of Mercedes Benzes and yellow mini-vans. One night, she walked past a Renault dealership and saw slides projected in a timed rotation against a building next door. She liked the different bicycles, especially the Prince models. Discovery – perhaps an overrated objective – could bring satisfaction. Learning that one city region was named Bezirksamt Eimsbüttel, she thought it was Turkish. She was wrong. She liked being wrong, just as she liked dressing in layers.

She splurged on sweaters at a clothing store, Wormland, on the Alster shopping mall. She bought fur-lined leather gloves. She watched new Metronom double-decker trains. She spotted one train, the Berlin Warsaw line that she’d seen for the first time in Berlin’s ZooBanhof. She found new bridges. She lingered when crossing them.

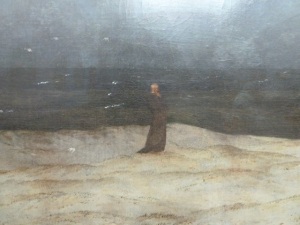

At night, she chain-smoked, read novels, and scribbled in her journal while steadily downing a cheap bottle of Riesling. On more than one drunken afternoon, she wobbled through the Deichtorhallen to view contemporary photography, or else the Kunsthalle with its famous collection of oils by Runge, and her discovery: Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Overlooking The Sea Of Fog. The loneliness in Friedrich’s masterpiece held her in thrall, capturing both what she was, and couldn’t be. Lost, wanting, gently heroic. Not tragic or dramatic but poignant. She bought a postcard of the painting and taped it inside her journal.

Along with art and train stations there was the TOB bus depot, a modern structure of curvilinear silver tubes and lightly tinted glass sheets. One day, she saw the ghost of her father there – white-haired in a gray scarf and matching flat cap. He rode a kid-sized bicycle with pannier bags.

Roter steher: red light signal. Grüner geher: green. She devoured Tillman’s books in English on film and German literature, learning that Brecht loved American detective novels and penned Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die. But Brecht meant Berlin. Claudia wanted Hamburg – eighth largest world port, allegedly home to more bridges than Venice. City of Brahms, canals, and BMWs speeding down cobblestone lanes. During the war, 80 percent of it was destroyed.

One morning a bicycle zipped by, grazing her leg. Lunging out of the way, she cursed until she realized she’d been walking in the bike lane. Steeling her nerve, she expected the cyclist to curse back at her. There was no such commentary.

It seemed the Germans of Hamburg walked and biked, but few appeared to be going anywhere. Claudia reveled in their aura of restraint – many were out to take the air, their destination irrelevant. Small groups mingled, waiting for lights to change. She never saw them jaywalk, and they often used a word that sounded like tooz. It had various levels of meaning as a way to show respect in public.

Claudia smoked where she pleased, bought coffee where she could drink from a ceramic mug to remember how her coffee tasted. She couldn’t find peanut butter anywhere. On Sundays, the quiet was so complete it disarmed her; she found herself looking for people and commotion

On weekdays, she visited the same bridge near the Eppendorfer Baum station, where she watched a woman panhandle for her cat and dog. Each pet sat in a box on the sidewalk. Attentive, disciplined, they looked as if trained to appear hungry. The woman held a sign that explained her plight. Euros fell into her basket on the ground.

At a different time of day, but on the same bridge, Claudia passed an old man cranking an organ grinder. She dropped a Euro into his cup. The man didn’t even look at her.

Another old man panhandled in a comical way; he beamed at commuters, not daring to offend, and his smile revealed traces of lunacy. Some handed him a coin as if he were a friend. Amiable, grateful, a fixture, he appeared to get by. He lacked the menace Claudia had seen in Manhattan panhandlers: their broken bodies camped on a sidewalk, their toothless faces leering.

How clearly from a distance she saw the native trappings that had formed her.

***

February would end. Claudia felt it. Sidewalks gleamed with snow pushed by volatile winds. Warmth meant everything, and so did trash receptacles. The white streets gleamed, spotless. The winds didn’t blow any trash. They carved ripples in puddles where ice had thawed.

The torpor of deep winter was passing into suggestions of change. Even at night she saw a growing brightness in the sky. She felt this brightness in glimmers of resurgence that stirred within her limbs. With each day, she walked a little further from Tillman’s apartment.

***

On her way to Innocentia Park, she said hello in English to a Philippine woman pushing two state-of-the-art baby strollers that smacked of Park Avenue West. Bundled against cold, a milky-faced child sat in each one, but it was the Philippine servant woman that held Claudia’s attention. Had she torn up her roots to work so far from home? No doubt, she had a story that needed telling.

The woman thought Claudia was English, maybe Australian. Flattered, Claudia told her New Zealand. Why be associated with those Yank tourists in Berlin at Checkpoint Charlie?

I know this woman. She nurtures hope in the wealthy children who will manage Germany’s future. Who knows the darkness she faces, and the ghosts and heartbreak she has left behind? Who tells her story?

I do, thought Claudia. The pain in her eyes shames me.

***

Hamburg Sparkasse: the name of a bank. Reisburo for travel agency. Geldautomat for ATM. Her allotted funds were running low, but she wasn’t ready to return. She’d wait for Tillman. She’d keep herself busier, especially at night. Classical music was everywhere, with first-class concerts from the likes of Ian Bostridge, and Helene Grimaud. She chose an inexpensive concert at the St. Nikolai Cathedral, where she heard the Hamburg Camerata perform as part of an ongoing celebration of Mozart advertised on kiosk billboards as Mensch! She was grateful the program featured only one Mozart piece. The Bach went down like honey.

After the concert, she admired the tarnished copper of St Nikolai’s green steeple. A new church, not a feature for tourists, it blended with the modesty of the park, and its call to safety. She returned the following day, a Sunday, and found the park full of children.

Hearing their cries, she felt herself glowing inside.

***

Off she wandered at night, all senses primed and ready, getting lost, absorbing. Still, the bridges called to her. She went to them. She discovered another church, a small one. A clock in its steeple faced the street. Below the clock, and above a small narrow brick door, was the date: 1751. She studied it from a bridge in Haynes Park.

In another direction, down the river beyond the boathouse, lay a series of small arched bridges. Along the riverbank stood copses of naked birches, their branches black against silver air. Weeping willows’ fronds hung close to the river, brushing its surface, reminding her of Shakespeare’s Ophelia.

Ghost Herman asked: Why not drown?

Lines of poplars planted as windbreaks ran between townhouses set back off the river. The steeple rose from the horizon but didn’t pierce it.

Old steeple, old country and sky.

Old Claudia.

***

Snow started to melt as the temperature climbed a few degrees above freezing. The sidewalks were swept by men in orange jumpsuits. Using leaf blowers, three at a time they moved through residential neighborhoods.

Claudia walked Eppendorfer Strasse overwhelmed by echoes from the dead. Had she changed? She wanted to know why, this time, the dead annoyed her. She rested in a Turkish embiss, sipping coffee. With each puff on her cigarette, she felt thinner. Why bother with suicide? Why not vanish and never return?

She looked out the embiss window down a curving avenue with buildings on both sides at the same height. Red tiles covered many roofs. She hadn’t expected this. The tiles seemed right for Florence, but reminded her how little she knew the city. Each day had brought new architectural treats. From steeply pitched narrow chalet fronts, to glass cube offices. She’d seen the gold memorial bricks mortared into sidewalks in front of houses where Jews had lived. Names, dates and professions of family members were etched into each brick with the date the house was blown up. In many cases, elegant houses had been built in their place.

In other holes in the city, she’d seen Bauhaus monstrosities erected next to fast food joints as if to say, sure, fire bombs had once wreaked havoc, but those days had passed. She thought these architectural vulgarities spoke a 21st century Esperanto that proved parts of the world were the same everywhere – a variation on a whore’s greed.

The flow of the buildings, as Claudia followed them down the avenue, reminded her of Regent Street in London. Yes, she’d been places, but to what end? What scared her was the sudden gravity she felt. She saw the avenue in flames. She heard the whistling of bombs. Heavy furniture crashed through windows. Diesel fumes fouled the air. Massive plumes of smoke concealed ravaged faces.

Not long ago, this was rubble. She told herself to sink in. To play her miniscule part. She had time enough for ghosts. Let them feed her.

***

Tillman’s living room featured a window that opened like a door to a balcony. Too cold for that balcony, so she ate standing up in the kitchen. She stared at three identical buildings of the Grindelberg neighborhood complex, all of them dotted with chinks of light. Paths ran between them lit by big round lamps. By day, bikes were ridden there, and mothers pushed strollers. At night, with high winds, there was a closed-in feeling.

Dangerous or not, Claudia needed to walk. Otherwise, she’d get drunk again and pass out. After eating, she put on her hat, coat and gloves and found her Manhattan stride. Alert, bold, unwilling to stop, she belched up fumes of the prosecco, camembert and sunflower bread she’d bought earlier in the Aldi supermarket. When she reached the Grindelberg Cinema, she read the marquee and read: Get Rich Or Die Tryin’.

She paused a moment. The mainstream American message had never been subtle. So what? She was thinking movies again, and enjoying it. She could smoke and drink in the lobby, take a beer inside and place it in a holder of her arm rest. At this cinema, American movies were screened without subtitles. Many Germans grasped English, and some spoke it better than Americans. Tillman was a perfect example.

As a woman over 40 in the show biz dance, was she a dinosaur? Was all of her angst about her aging? Was she really that banal?

Perhaps so.

Her insignificance was humbling, but she had to remember that the choices in the movie biz were made behind the scenes. She had to love something bigger than herself. She’d loved film since a ten-year-old, when Dad had given her his old video camera. She could remember how that camera smelled when it heated up. The weight of it in her hand.

In it for the long haul – a frigid trip, indeed. If there were compensations, she had to find them. Ghost Herman remarked: You’re a dreamer, Little One.

***

Wind blew in off the harbor and Claudia listened as it raced into gaps between buildings. The shine of the air, so opalescent, reminded her of sheared coal. It gleamed in snow-crusted walkways that wormed bluish and crystalline between Grindelberg’s high narrow block buildings. Built of prefab concrete and without flair, they were home to small dramas lived behind curtained windows. She’d seen such windows all over the world. A few were still lit, perhaps still hopeful. Most were dark, with sleep as a blessing.

The complex was a government project carried out by British soldiers and funded by American money. It had been built for British officers, but according to Tillman the Brits hadn’t stayed. They’d had their own country to rebuild. Where had she read that Brits lost 85 percent of one generation in that war?

Why wade in the past? What of the Padaung women of Myanmar, their elongated necks trapped within stacked rings, unable to flee to Thailand? What of the 10-year-old girls working 14-hour days without breaks in the sweatshops of Shenzhen, China? She’d visited Shenzhen. She’d seen those sweatshops.

It hurt to be informed, and to care. It didn’t hurt to jump off a bridge.

You’re a fool, said Herman.

At least she was starting to know it.

***

Hers were ginger steps over black ice pooled in walkways between the block buildings of Grindelberg. Across the city in the Reepersbaum, night meant a carnal splurge for the young that would make Fassbinder smile. Not here, where angels wheezed through nightmares on sullen mattresses, and a blunt dawn came early with the seagulls. Here, Tillman’s Mom lived with memories of her husband, killed in a U-Boat during Black May.

Tillman had said that Mom kept in a box the handful of photos, receipts and postcards that weren’t destroyed. Claudia had never seen this box. She didn’t want to. Every photo and hand-written card would only remind her that all wars remained an abomination. Still, she hoped Tillman’s Mom guarded that box under the rafters of what defined her buried life. Claudia felt comfortable hoping this, because she kept her own box and thought it a morgue and a jewel. More than a reminder of who she’d been, it was a country to visit, and to flee from.

Once a traveler, always.

It was a bridge.

***

How narrow the elevator in Tillman’s building. Shaped like a domino, higher than wide, a box within a box, three big bodies would make the ride uncomfortable. So she didn’t take that elevator. She seized the stairs two at a time, huffing into a smoker’s cough.

***

In a flat wool cap worn backwards, Claudia looked like a newsboy out of the 1940s as she loitered under the I-beams of Hamburg’s U-Bahn railway between Dartmoor and Eppendorfer Baum. Every Tuesday and Friday, there was an outdoor market at this location, rain or shine. Market vendors had arrived at dawn to sell fruit, cheeses, herbs, fish and meat. The BMWs and Volkswagens usually parked under the railway had to be moved to make room for semi-trailers, vans, compact pick-ups and diner wagons lined up end to end up along both sides of the paved walkway under the U-Bahn tracks.

The food on display opened Claudia’s eyes, and so did the cars that had been forced from their usual spaces. Here were Land Rovers and Porsches. In this neck of Hamburg it appeared Germans were living well.

She bumped along behind a middle-aged couple. The man wore leather shoes and a camel hair coat. His wife wore a fur with a cashmere scarf. They shopped as if they had nothing but time. Claudia envied the gravitas in the way the older man moved, his arms locked behind his back. In Manhattan, he’d get bowled over. Not here, where one could enjoy the smell of oranges so radiant in their neatly stacked pyramids. Their color was a comfort in the cold.

Fumes from fragrant pastries teased Claudia’s appetite. Here, she could learn to eat again. Eating would help her sink in rather than vanish. Slabs of roseate fish fillets gleamed under portable lamps. Coiled links of sausage proved with their crimson skin that they were freshly ground. A sudden dose from an exotic cheese blended into the aromatic mix lingering in gelid air. It seized Claudia, dazzled her, and she felt invigorated. This, the European way – out in the open and without alacrity – allowed quality to take precedence.

A train rolled by overhead, and for a moment Claudia went joyfully deaf. Lips moved and gloved hands gestured. It was a Lillian Gish silent. Soon, the action would shift to a station. A train in black and white, shadowy and promising, would steam into the frame.

That era had passed, and so had the train. Claudia caught herself smiling and wondered if this was happiness. Market banter expanded around her. Aromas lingered as vendors measured grams over their scales. One old gent tipped his hat to an acquaintance. He sampled cheese conspicuously, in a mannered way. Claudia didn’t see lumpy backs or cheeks with boils, or broken teeth. There were no Turks. If so, they sat in cabs. The shoppers looked fit, well-preserved, as much on display as the food.

She liked such a market for its pace and civility. The women vendors wore crisp aprons. Their hair bright blonde, eyes blue as cobalt. The men durable and tested in their bloodied aprons, their square-tipped fingers around big cleavers as they hacked at chunks of meat. This was a slice of Hamburg, and she revered how it moved – far too slowly to be American.

When had she last wanted to eat? But she wouldn’t buy groceries here. She’d keep to her budget at the Aldi market in her neighborhood along Grindelallee. Everything was cheaper there. A less polished clientele crowded the place each Saturday morning, and she suspected most of them didn’t care if their vinegar had been made from organic sherry.

Ironic, on the other hand, to think that without globalization and the EU, the Aldi market chain wouldn’t have been possible. According to Tillman, two Italians had founded it. No one seemed to mind. Economics 101: affordable groceries won hearts and minds around the globe.

She was hungry, and thinking of food as more than necessity. Indeed, change had come.

***

Tillman returned. If only, thought Claudia, to read the clockwork of his mind. He stood a few inches over six feet. Broad-shouldered, with a raw meatiness to his face, his ears stuck out in a charmingly impish way. He was half bruiser, half cherub. All there.

Claudia beamed upon their meeting, but no smile came from Tillman in return. No hug, no handshake. In the kitchen, he remained stoical, white-haired, his feet evenly apart, and he looked down on Claudia with skeptical slate-blue eyes. He had been all over: from Bali, to Thailand, and India. His favorite American city – and he’d seen many – remained San Antonio.

They were both travelers, thought Claudia. Brother and sister in some ways. She could tell him anything. It got bad when her Mom died, and Tillman had been there to listen, and to recommend a therapist.

Tillman had also chosen her as the one to share his early struggles with alcoholism, and his homosexuality. After AA, he’d begun reading Krishnamurti and practicing meditation. Written on scraps of paper tacked all over his Brooklyn apartment was the maxim: All people suffer deeply.

Tillman remarked, “When you get back, you will find your phone and a list of calls on the table. One of the calls I answered. It was from Juniper Resnick.”

Claudia’s face went flush. Her eyes bloomed. “Seriously?”

Tillman nodded. “She wants another meeting about the Myanmar project.”

With a shriek, Claudia lunged for Tillman and hugged him. “We have to celebrate.”

Tillman, ever phlegmatic, pulled himself away. “She thinks Susan Sarandon might come aboard if you let Tim Robbins narrate. She also said she hopes you like Hamburg.”

“I’ll always like Hamburg,” said Claudia. “I really got to see it.”

“It’s fate,” said Tillman.

“No,” said Claudia. “I went after it. Look what happened?”

“What?” asked Tillman. “Tell me.”

She said, “Don’t I look hungry? I could eat a horse.”

They didn’t share a meal. Tillman, exhausted, needed time with his mother. He’d turn in early. Could Claudia wait until tomorrow?

She smacked a big kiss on his cheek. “I’ve waited this long. What’s another night?”

***

Tillman raised a glass of sparkling water, toasting travelers of the world, warm nights, cold lovers, and dreams of seahorses. Claudia raised her wine and toasted skipping gym class, and Daniela Vinge, her first crush.

Tillman stared at Claudia. He looked worried.

“I’m okay,” said Claudia. “It’s made a difference.”

“I know it isn’t easy,” said Tillman.

Claudia, comfortable as philosopher in Tillman’s presence, said the search for a home drove all lost souls and made her prone to self-pity just like any sojourner. She’d wanted less to die than to die publicly. That was why she was so thin. Someone had to see her wasting away.

Feeling herself letting go, Claudia laughed as she ordered another glass of wine. Tillman leaned over the table and told her that one paid and lost, and paid again. All were, to some degree, failures.

“Nothing is fixed,” he said. “Travel is our natural state.”

“How do you do it?” asked Claudia.

“I care about others more than myself,” he said. “And I do something about it.”

***

She had him to thank for being alive. She didn’t want to leave – not Tillman, Hamburg, or her dark winter nights alone – they all meant something profound. She had her suitcase shaped like a box, but it was empty. She was leaving everything behind. She planned to return at least once a year. She had to walk those bridges in summer.

She’d made her first phone call. A therapist appointment for the day after her arrival.

Snow fell in fine pellets, not quite rain, swept along by uneven sea breezes. She heard seagulls, but she couldn’t see them. Hunger pangs erupted as she walked past a Turkish-run eatery with squares of lasagna in its window.

She paused to envy one last time the hardiness of cyclists who pedaled in the proper lane. An earthen smell startled and comforted her, along with the sight of tulips, gladiolas, and other tall annuals put out for sale on the street in front of a shop. She saw hand tools, gloves, tin and copper planting boxes meant to hold flowers in place.

Spring would come to bust them open. Spring was a form of home. She wanted to share this thought with Tillman. With the world. But how? She’d have to produce another film. It was the best way she knew. It was why she’d survived.

They spent their last night at the Birdland jazz club on Gartnerstrasse 122 and listened to the Boris Netsvetaev Trio. With each pause in the music, whether disjointed or cerebral, Claudia felt pieces of herself expanding inside her body. She couldn’t say she’d be able to use those pieces or even reassemble them. She could say she hungered now, and welcomed time pressure, neurosis, and talk for the sake of talking – as if she’d never seen a therapist in her life.

Her story, like many others, was one of motion, after all.