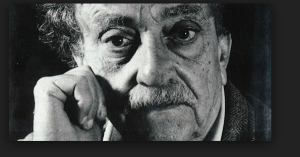

Dialogue with Kurt Vonnegut

Anarchist and Social Critic

By Gaither Stewart

(Note: After my early enthusiasm about the writer and man Kurt Vonnegut, I became skeptical of his skepticism. Was he a phony, I began to wonder? After I met him, his life style in his sumptuous Manhattan East Side town house bothered me and seemed to belie his satires of that same life. Even the adoration for him in Europe at the time sharpened my suspicions that he was perhaps not what he seemed to be. Despite my admiration for him the writer, the satirist, the anarchist, still for some time after our two meetings in the middle 1980s, I wondered if his claim that he belonged to the establishment because he was rich was not somewhat jaded. I wondered about his “positive nihilist” role. What exactly did that mean? It just took me time to make full circle and again see him for what he was. What in the end endeared me to Kurt Vonnegut was his unwavering attack on the “American way of life” and what it has engendered in the rest of the world.)

I somehow thought Vonnegut would last forever, charming as always, joking, teasing, mocking, prickling, criticizing so wittily that the target of his pungent irony thought he was kidding, praising so ambiguously that those he loved thought he was criticizing, throwing mud pies in the faces of the powerful and calling them names, and boasting to one and all that he made lots of money being impolite.

“I most certainly am a member of the establishment,” Vonnegut told me that day over two decades ago, I think it was the fall of 1985, in his town house on the East Side in Manhattan. An Amsterdam magazine had sent me to New York to interview the light of a “certain” American literature who so titillated, amused and charmed Europeans by ridiculing the ridiculous sides of America by his playful lack of reverence for institutions and authority and for all the things that too many people take too seriously.

“No one is more in its center than me but I don’t maintain contacts with the other members. Though I don’t feel solidarity with it, I admit membership and I don’t like establishment people who play at the false role of rebels. Then the establishment needs people like me— however I’m a member only because I have money, otherwise they wouldn’t even talk to me.”

At the appearance of his first novel, Player Piano, in 1952, in the same year that Hemingway published The Old Man and the Sea and Steinbeck brought out East of Eden, Kurt Vonnegut was thirty and still widely considered an underground writer, despite Graham Greene’s labeling him “one of the best living American writers.”

Kurt Vonnegut (born 1922 in Indianapolis, died in New York, April 11, 2007 from the consequences of a fall two weeks earlier) was a very humorous man, so entertaining that he was deceptive, marked by broad grins, soft delivery and false modesty. I wondered, as his co-establishment members must have wondered, too, where the creative artist ended and the performer began. Or vice-versa. Was he a real social critic or simply a cynic?

After he became widely known in the sixties Vonnegut was identified with the revolt against realism and traditional forms of writing. Though he most certainly was a “social writer” from beginning to end, he was also more experimental than his contemporaries like Norman Mailer, Philip Roth and John Barth, more fascinated by the absurd and the ridiculous. His science fiction and short stories that had appeared in the best magazines in the post-war years, Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, Playboy, Colliers, Cosmopolitan, Saturday Evening Post, were marked by parody and ridicule. A cult grew around him, especially among youth, so that he remained “mysterious” even after he no longer belonged to the underground. The appearance of each of his subsequent books was an event and he remained a fresh writer.

Things got underway in earnest already in that first novel. Vonnegut’s admiration for the marvels of technology had resulted in his early bent for science fiction, of which he wrote a lot. In Player Piano he was “fascinated by the wonderfully sane engineers who could process anything … do anything on their own horizontal level. Miraculous what the engineers could do. They were brilliant but didn’t seem to do anything brilliant.” Drawn on Huxley’s Brave New World and science fiction in general, Vonnegut’s concern was that these specialists, each working in his own field, would soon produce their own leaders, a caste created by a technocracy barren of leaders capable of working on a vertical level and devoid of fresh humanistic ideas.

“Precisely this scientific system created our leaders. The problem is they brought little ideology into the factories. In general there is so little ideology left … if we ever had any at all. It’s good that we at least appeal to justice. On the other hand, I have found that one can behave ideologically within a small group related by profession or interests. I’m fascinated by the Paris Commune for example, especially its branch of anarchism. People tend to hang onto natural anarchy. The life of Bakunin is useful. Seen as useful people, anarchists offer a fascinating alternative to big government today. When I was a prisoner of war in Germany my small labor unit was left to fend for itself in destroyed Dresden. (One of his most famous novels, Slaughterhouse Five.) We dealt effectively with the thieves among us without being ferocious. We did that intuitively.”

That was Vonnegut.

One of his contorted Americas is controlled by one enormous corporation-state under the guidance of an ugly old girl whose weighty signature is her fingerprints (Jailbird). In this society the poor spend their time squirting chemicals into their bodies for the simple reason that “on this planet they don’t have doodley-squat.” That was the society that concerned the writer, Kurt Vonnegut, searching for a place for the individual. Like himself his characters are amusing, entertaining and sympathetic … and rebels all.

Yet his conclusions are seldom humorous.

“Big government is like the weather, you can’t do anything about it. People are moving away from central authority and its ineffective bureaucracy, which has created too many artificial jobs in Washington to accommodate our children. Then, let’s face it, leadership is so poor.”

In fact, Vonnegut spent his later years attacking that bureaucracy, especially the George W. Bush administration.

His artistic family background—his father and grandfather were architects, his daughters painters—and his association with painters and musicians, engendered yearnings in him for the image of the Renaissance man. The day I spent the afternoon and early evening with him he invited me along to check in at the Greenwich Village gallery that was showing fifty of his book illustrations that he called “doodles with a felt-tip pen”. At the vernissage the vain writer-illustrator was as nervous as a Broadway musical star on opening night.

But not to worry! His fans snapped them up at one thousand dollars each.

He must have chuckled all the time to himself. That exhibit was the stuff of a typical Vonnegut literary vignette as in Breakfast of Champions in which he pokes fun at the art world, phony artists and gullible consumers in a mixture of ambivalence and pity. His artist Karabekian has been paid $50,000 by the town for sticking a yellow strip of tape vertically on a piece of canvas. The whole town hates him for the swindle until he explains that it was an unwavering band of light, like each of them, like Saint Anthony.

“All you had to do was explain,” say the relieved people to their cultural hero, now convinced they have acquired one of the world’s masterpieces. “If artists would explain more people would like art more.”

Though Vonnegut repeats that workers simply want an explanation, the cynic suspects cynicism in him too.

“Sometimes I think the people of the world are begging to understand. And to be understood by the United States. They want to be understood more than they want to be ‘freed’ by America. Actually the US encourages not seeing other peoples. Disregard for other peoples is a matter of education. Making money is the point. Don’t waste your time. Conserve your resources. Withhold your time from people who can’t reward you. This started when Reagan came along and did away with social help using tax monies that Roosevelt’s New Deal had introduced. So the poor are now up the creek! (This was 1985, remember, before Iraq and Afghanistan and Iraq and East Africa and the war on terrorism.)

“And our intellectuals didn’t react at all to his re-election,” says the self-proclaimed Socialist-anarchist. “He ran unopposed.”

In Deadeye Dick a neutron bomb being transported along the Interstate goes off, killing 100,000 people of the town but leaving everything else intact. After the dead are buried under the parking lot for sanitary reasons, the question is what to do with the contaminated area. Someone proposes moving Haitian immigrants there. The point is that Vonnegut’s technological society needs the workers but it cares even less for non-Americans than for its own citizens.

“I’m convinced that slavery will come back, and Haitians were after all once slaves. With all the automation, society needs slaves. One will perhaps have the option of selling one’s services for long periods, thirty years, or for life. There will be many takers. Like the Asians and Mexicans who work here now for less than minimum wages.”

Americans who make their lives abroad see this generalized blindness to other peoples in their fellow Americans quite clearly, though they themselves are apparently unconscious of the neglect. I think Vonnegut must be right: it’s education … and the brainwash and spin, too. Tourism and travels to Europe and Asia and South America to photograph the natives don’t really correct the blindness; sometimes it reinforces it.

We’re drinking scotch and black coffee and chain smoking in the kitchen of his unpretentious but large and expensive townhouse—four stories, with garden—in a swanky pretentious area of Manhattan. A cold wind is blowing down from among new high-rise buildings. Long Vonnegut in baggy pants and wool shirt is sprawled on an iron garden chair, drawling out his witticisms, descriptions and pronouncements, candid and down-to-earth, having fun at the expense of everyone—himself, me, us and them—the artist and social critic and performer, too. He runs his slim delicate fingers through long reddish hair and pulls nervously at his mustache. His talk has the quality of being quiet and breath-taking simultaneously. He seems and acts younger than his years.

“I am successful,” he stresses, returning again and again to the money thing. “Privileged! When I was young and working for General Electric I was a hostage of society because I had six children. Now I’m free because I have money. I don’t like the privileged class, in the same way I will always resent the officers class. I was a private during the war and saw an infantry division wiped out its first time in combat because it was poorly led. Like America is poorly led today.” (Reading the write-ups of the two interviews I did with him in 1980 and again in 1985 is a curious experience; much of what he had to say then he could have said this year.)

Like many writers Vonnegut said that writing for him was a way to rebel against his parents’ life style. He claimed he chose writing because he wrote better than he painted, and because you have to do something to make your mark. He liked writing for newspapers because of the immediate feedback, which plays an enormous role among journalists I have known. Journalists are as vain as novelists and find it rewarding to write an article in the evening and see it in print the next day. I liked, appreciated and agreed with his social stance but he was his most entertaining and I believe most in earnest speaking of the arts.

“You can’t help but look back wistfully to the days of Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci who worked in many arts. But today there are so many things to do that we don’t have the time to dedicate ourselves wholly to the arts. Still, I believe in the arts. My children say I dance well. I can shag and that’s mysterious to the young. I can jitterbug and that impresses them. And I play the clarinet lovingly. In general the arts have held up well in catastrophic situations. Yet there are preferences. It’s true that painters like to paint and writers hate to write. Putting paint on a canvas is fun and is easy. You don’t even have to finish it. After six strokes you have a painting. At that point you can frame it and hang it. Maybe that’s why writers like to paint and draw. Norman Mailer is a good drawer. Tennessee Williams does good watercolors. Henry Miller is the best writer-painter I have known. Poetry too is fast. That’s why poets have so much time to sit around cafès and talk. But the novelist is always busy, sitting at a typewriter like a stenographer, which is boring and lonely.

“My book, Breakfast of Champions, is about art. I think art should be refreshing to everyone. But many artists are in league with the rich to make the poor feel dumb, like all the galleries downtown with walls covered in dots and blank whites. The rich organize art in such a way as to prove they have different souls from the poor, to give a biological justification to their status. Mystification is the secret. Ruling classes find it politically useful that workers can’t understand the pictures in the galleries. Inaccessible art grew out of industrialization. In the Renaissance art was of the people.”

Vonnegut’s heroes are outsiders, the rebels in big organizations who think the system is wrong and maybe want to change it. In a wacky and comical way he depicts the hopeless and sad human condition. His heroes care about involvement. Yet they are helpless. They have little power to decide anything.

“No man is in control,” he murmurs. “People are just born on this planet and are immediately hit over the head and yelled at. Ten per cent of the world’s children are abused. So what chance does man have? My own success is like an American dream. My growth graph is perfect. I’m prosperous. I can see clearly how it worked for me. I’m convinced we’re all programmed in a certain way. Still, big bureaucracy appalls me. Gore Vidal was right that this is the only country in the world that does nothing for its citizens. Jobs don’t go around. The auto industry is laying people off (that was twenty-two years ago and it still is!). Still, I have to say that working on the assembly line is better than doing nothing at all. But the problem is we’re just not useful anymore. We need to find new uses for man, find a simpler way of life.”

The backdrop of Vonnegut’s stage is this: While the people lament gasoline prices and call for small cars, Detroit turns out bigger cars and lays off workers. The people eat macrobiotic foods and squirt chemicals up their assholes and swallow exotic anti-hemorrhoid salves. It’s the people! But not people in his beloved New York. His settings are the wide expanses of America. Where the really funny, mad things happen. A world so far from Europe as to be incredible. A world that baffles Europeans.

At a certain point, still in the kitchen, and after his wife had glanced in a couple times, I think to check on the scotch level, and after he told me he never gave interviews to the American press, only to Europeans, and pouring more scotch said that interviews were hard work, and after he admitted he neglected his German heritage and the Vonnegut family tree in Münster, I asked him about his statement in a recent book—I don’t remember which—that people and nations have their story that ends, after which it’s all epilogue, and he intimated that the US story ended after World War II.

“That was only a joke,” he said wryly, smiling sheepishly.

“It didn’t sound like a joke. It sounded quite serious.”

“Well” (reluctantly, perhaps not wanting to appear too critical of the USA to the European public), “the United States story will become epilogue unless it succeeds in renewing itself. Like a play peters out if it slows down and has nothing else to say. One must invent new themes for development. Economic justice is one such theme that would make our first two hundred years seem like only Act I. That would become Act II. If that theme is not developed, then our story peters out. Our legal justice would then become mere mockery. Remember the old quip: ‘It’s no disgrace to be poor but it might as well be.’

“In the Constitution there is nothing about economic justice, only the legal utopia. The Bill of Rights is a utopia. We have laws that violate the Constitution. It’s now time to start thinking about social fairness. Our superstar government leaders deal with billions of dollars and we have individuals richer than the whole state of Wyoming. The military-industrial complex is robbing us blind, building their bizarre weapons that costs $40,000 a shot to use. Sensitive weapons that don’t work in the dark or under 50°. We can’t possibly understand all that crap. Compare the arms manufacturers to the salesmen of snake eye in the frontier days. The miracle medicine. In the 1930s we had Eugene Debs who labeled arms manufacturers ‘merchants of death’. Then the crooks took over the labor unions and we have nothing left today so that I don’t have a banner to which I can adhere. And the same type of people are on top in our society today, selling their quack remedies, to protect us against the dread disease of Communism. (I’m certain he said the same about terrorism in later years!) And that’s what I say in my annual lectures at ten universities. I would like to see that change.

“Yet people don’t give a damn about anything. Few care what we pour into the world everyday. Few care if we go to war. People are embarrassed about life and don’t care if it all ends. Humans have decided that the experiment of life is a failure.”

One of his characters speaks of being born like a disease: “I have caught life. I have come down with life.” Speaking about experiencing the destruction of Dresden, a city of beauty like Paris, Vonnegut said he was the only one there who found it remarkable that it all went up in smoke. “Not even the Germans seemed to care.”

The scotch flowed. The kitchen was blue with smoke. Thank God I was recording our talk or little would have remained. At some point one of us said “doodley-squat.” He loved those sounds, spicing his novels liberally with skeedee wah, skeedee wo. At critical moments his heroes mumble in skat talk of the jazz era, skeedee beep, zang reepa dop, singing a few bars to chase the blues away. Then, yump–yump, tiddle-taddle, ra-a-a-a, yump–yump-boom. And abbreviations Ramjac, epicac and euphic. Onomatopeic or symbolic nonsense. Doodley-squat for the nothing at all the poor don’t have.

It all sounded OK in the smoky blue kitchen over scotch but what do those sounds mean? Futuristic concepts? Or sounds of joy or despair? The voice of truth? Or just social chatter? Escape or mere foolishness? Is he writer or entertainer?

“Any agreement on the basis of friendliness obliterates ideas and thinking. What about that?”

“Yes, I wrote that. The stupid performance of man and his degeneration are possible because no one is thinking. There has been a warm brotherhood of stupidity. What do words mean anyway? The old Hollywood joke is expressive:

Question: How do you say, ‘fuck yourself?’

Answer: ‘Trust me.’”

________

I took the following information from various websites, Dutch, German and Italian, of countries where Vonnegut was immensely popular, simply in order to round out his life story. After his last novel in 1997 he left fiction writing and became a senior editor for In These Times. The magazine is dedicated to informing and analyzing popular movements for social, environmental and economic justice; to providing a forum for discussing the politics that shape our lives; and to producing a magazine that is read by the broadest and most diverse audience possible. Vonnegut wrote that if the magazine didn’t exist he would be a man without a country.

In his columns there he began a blistering attack on the administration of President George W. Bush and the Iraq war. “By saying that our leaders are power-drunk chimpanzees, am I in danger of wrecking the morale of our soldiers fighting and dying in the Middle East?” he wrote. “Their morale, like so many bodies, is already shot to pieces. They are being treated, as I never was, like toys a rich kid got for Christmas.”

In “A Man Without A Country” he wrote that “George W. Bush has gathered around him upper-crust C-students who know no history or geography.” He did not regard the 2004 election with much optimism; speaking of Bush and John Kerry, he said that “no matter which one wins, we will have a Skull and Bones ( a secret society at Yale University) President at a time when entire vertebrate species, because of how we have poisoned the topsoil, the waters and the atmosphere, are becoming, hey presto, nothing but skulls and bones.”

In 2005, Vonnegut was interviewed by David Nason for The Australian. During the course of the interview Vonnegut was asked his opinion of modern terrorists, to which he replied “I regard them as very brave people.” When pressed further Vonnegut also said that “They [suicide bombers] are dying for their own self-respect. It’s a terrible thing to deprive someone of their self-respect. It’s [like] your culture is nothing, your race is nothing, you’re nothing … It is sweet and noble — sweet and honourable I guess it is — to die for what you believe in.”

Vonnegut’s novels

-

Player Piano (1952)

-

The Sirens of Titan (1959)

-

Mother Night (1961)

-

Cat’s Cradle (1963)

-

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, of Pearls Before Swine (1965)

-

Slaughterhouse-Five, of The Children’s Crusade (1969)

-

Breakfast of Champions, of Goodbye, Blue Monday (1973)

-

Slapstick, of Lonesome No More (1976)

-

Jailbird (1979)

-

Deadeye Dick (1982)

-

Galápagos (1985)

-

Bluebeard (1987)

-

Hocus Pocus (1990)

-

Timequake (1997)

Short Story Collections

-

Canary in a Cathouse (1961)

-

Welcome to the Monkey House (1968)

-

Bagombo Snuff Box (1999)

Essays

-

Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons (1974)

-

Palm Sunday by Kurt Vonnegut, An Autobiographical Collage (1981)

-

Fates Worse than Death (1991)

-

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian (1999)

-

A Man Without a Country (2005)

Theater works

-

Happy Birthday, Wanda June (1970)

-

Between Time and Timbuktu, of Prometheus Five (introduction by Vonnegut) (1972)

-

Make Up Your Mind (1993)

-

Miss Temptation (1993)

People have long forgotten all the carnage on the battlefields and cities of WWII. Vonnegut, an infantryman at the battle of the bulge and a POW, was one of the first and nearly the only author to write critically about the US role in the war. He was joined by Joseph Heller in pointing out the futility and horror of war; placing the US military -economic-political-complex at the center of the criticism. The US was almost universally seen as the “good guys” after the war and whatever means they used to achieve victory was justified–including the use of nuclear weapons on Japan.

We saw both Bush administrations cooking up wars, and now the Obama administration seeking any excuse to attack the Syrian regime for use of chemical attacks. This finger pointing is the ultimate hypocrisy.

Today, as seen by the profusion of US manufactured wars, use of drone attacks, and the mainstream media’s utter failure to provide self-criticism is a very large hint that the US media and society has regressed into a flag waving, chanting, pool of ready-made, potential mercenaries.

All the lessons we should have learned by reading Vonnegut or Heller and the Vietnam experience or even the Russian experience in Afghanistan are long gone. I feel like the naked Yossarian in Catch-22. And, I am looking for a tree to sit in to watch this debacle.